The following study on the international relation of investment, savings and economic growth is based on a paper produced by the author, John Ross, for Antai College of Economics and Management, Jiao Tong University Shanghai. It originally appeared on the blog China in the International Financial Crisis.

Introduction

This is the first of two papers devoted to the evidence on the relation between investment, savings and growth with particular regard to present economic issues facing China in relation to the international financial crisis. The two papers, although interrelated, are produced separately for the following reasons.

The first paper is an historical and comparative examination of the factual relation between investment rates and economic growth rates. The economic evidence it produces is clear. A very high rate of investment is required for rapid economic growth of the 8% a year level China requires. It is a high level of investment, not a high level of consumption, which is indispensable for rapid economic growth rates – there are no examples of countries with low rates of investment and very high economic growth. Those who argue that China, to maintain its level of economic growth, must increase its consumption level and reduce its rate of investment must produce evidence to justify that claim – and will be unable to do so.

However, from an underlying strategic economic issue such as the above, it is not possible in a one to one mechanical way to derive immediate policy conclusions – something the present author is acutely aware of from both theoretical considerations and practical experience. In order to judge a specific immediate policy it is necessary to have not only an overall framework but also detailed knowledge of concrete economic circumstances. The issues dealt with here affect economic strategy and other concrete factors must be taken into account in framing short term economic policy responses.

Investment and savings

In relation to the international financial crisis significant discussion has taken place regarding the US and China’s savings rate. However, from the point of view of China’s economic growth rate, the issue with the most direct effect is China’s rate of investment. The savings’ rate’s effect on growth is indirect.

This distinction may be easily illustrated by noting that while savings are necessarily required to finance investment it is both theoretically and practically possible, for example, for a country to have a high savings rate but to have relatively low or moderate investment and economic growth rates – Saudi Arabia and Libya are examples. In such cases a high savings rate is not used to maintain a high rate of domestic investment, with an associated high rate of economic growth, but instead foreign assets or exchange reserves are accumulated.

It is therefore investment which directly affects the rate of national economic growth. For that reason, regarding the potential for strategic economic growth, analysis should commence with the investment rate.

Confusion of domestic demand and domestic consumption

This strategic issue relates to a further, more immediate, economic question. In sections of the media stimulation of ‘domestic demand’ is sometimes treated as though it were the same issue as the stimulation of ‘domestic consumption’. This is self-evidently theoretically false. Domestic demand consists of two components, investment and consumption. Stimulation of domestic investment is just as much stimulation of domestic demand as is stimulation of domestic consumption.

The consequences of different allocations of GDP resources to investment and consumption are, however, extremely different from the point of view of China’s economic growth. As will be seen in detail below a very high level of fixed investment in GDP is a precondition for a high economic growth rate in any country - including China. Lowering the proportion of China’s investment in GDP, that is raising the proportion of consumption in GDP, will lead to a much slower rate of growth of China’s GDP. From this more immediate angle also the first key macro-economic issue that should be examined is the investment rate.

This paper, therefore, examines the relation of the rate of investment and the rate of economic growth both from a fundamental historical perspective and from the point of view of the recent international experience of high growth rate economies.

The tendency of the proportion of the economy devoted to fixed investment to rise

Considering first the investment rate from a long term historical perspective, one of the most factually well established historical trends of economics is that the proportion of the economy devoted to fixed investment historically rises with time - and that this rise is correlated with increasingly rapid rates of economic growth.

This process can be clearly measured over a three hundred year period, and can also be seen to operate dramatically in the period since World War II. All major economies that have grown rapidly have a high level of fixed investment. There are no examples of major economies which have grown rapidly with a low rate of investment.

These facts have evident conclusions for the discussion of the model of economic growth and for China’s investment level.

After considering this from the point of view of a long timescale, setting out the factual data, it will be examined from the point of view of the experience of high growth economies since World War II.

The historical trend of the proportion of investment in GDP

Figure 1 shows the percentage of fixed investment (gross fixed capital formation) in GDP for a series of major countries over the longest periods of time for which data is available.[1]

Figure 1

The pattern is evidently clear and striking. By far the strongest trend is for the proportion of GDP devoted to fixed investment (gross domestic fixed capital formation) to rise with time. This in turn, as will be shown, is associated with progressively rising rates of economic growth.

The historical correlation of increasing proportions of GDP devoted to investment with rising rates of GDP growth

Considering this historical trend in more detail, and analysing countries in the chronological order in which a new peak in the proportion of GDP devoted to gross fixed domestic capital formation appeared, the following is the historical pattern.

- Commencing with the period immediately antedating the industrial revolution, the proportion of GDP devoted to fixed investment in England and Wales, at the end of the 17th century, was 5-7 per cent. [2] This rose slightly, although current estimates are that it did not rise greatly, during the 19th century - peaking at over ten percent of UK GDP prior to World War I.

This level of investment was sufficient to launch the first industrialisation of any country but at a rate of growth which, while unprecedented at the time, was extremely slow by contemporary international standards - about two per cent a year.

- Turning to the latter part of the 19th century, the proportion of US GDP devoted to fixed investment had risen to considerably exceed that for the UK – reaching a level of 18-20 per cent of GDP by the last decades of the century.

A sharp fall in the proportion of the US economy devoted to fixed investment commenced in the late 19th century, and was particularly pronounced during the period between World War I and World War II – being associated with the great depression of the inter-war period. After World War II the US resumed its pattern of 18-20 per cent of GDP being devoted to gross fixed capital formation. This generated an average growth rate of 3.5 per cent a year. With such a growth rate an economy doubles in size every 20 years and quadruples in size every 40 years. It was on the basis of this historical level of investment, and growth rate, that the US overtook Britain to become the world’s greatest economic power.

- In the period following World War II Germany achieved a level of fixed investment exceeding 25 per cent of GDP – peaking at 26.6 per cent in 1964. This period 1951-64 was that of the post-war German ‘economic miracle’ with average growth of 6.8 per cent a year - with such a growth rate an economy doubles in size every 11 years and quadruples in 22 years.

- Starting at the beginning of the 1960s Japan achieved a level of gross domestic fixed capital formation of more than 30 per cent of GDP. This reached a peak in the early 1970s, at 35 per cent of GDP, before later sharply falling. During the period of a high and rising rate of investment in GDP the average annual rate of growth of the Japanese economy was 8.6 per cent.

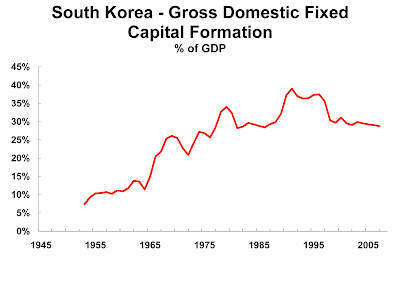

- From the 1970s onwards, South Korea similarly achieved a level of fixed investment of 30 per cent of GDP. During the 1980s this rose above 35 per cent of GDP. The other East Asian ‘Tiger’ economies – Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan – showed a similar pattern. South Korea’s economy confirmed the relation between fixed investment and economic growth illustrated by Japan by growing in this period by an average 8.3 per cent a year.

Such growth rates in Asia showed that something unprecedented in human history was now possible – that it was possible to industrialise an economy, and achieve a ‘first world’ level of development, in a single generation.

- From the early 1990s onwards China achieved sustained rates of fixed investment of 35 per cent of GDP with, from the beginning of the 21st century, this rising to more than 40 per cent of GDP – a level never before witnessed in human history. The result was average 9.8 per cent a year economic growth over a sustained period – also the most rapid sustained economic growth ever seen in human history.

- To complete the chronological picture, the proportion of GDP devoted to fixed investment for two countries recently undergoing rapid economic growth, India and Vietnam, is shown. The proportion of Indian GDP devoted to fixed investment has not reached the Chinese level but has become high – reaching 33.7% of GDP in 2007 and 37.6% of GDP by the second quarter of 2008. On this basis, in the last five years, India has achieved an average growth rate of 8.8 per cent a year.

In Vietnam the proportion of GDP devoted to fixed investment rose from 13 per cent in 1990 to 25 per cent in 1995 and then to 37 per cent in 2007. Economic growth has accelerated rapidly, rising to an average of 7.9 per cent a year in the five years up to 2007.

Considering these trends, such a high level of investment is a necessary condition for rapid economic growth. No substantial country without comparable high levels of fixed investment has achieved such rapid rates of growth on a sustained basis. But while such a high level of investment is a necessary condition for rapid economic growth it is not a sufficient condition. Other elements which must accompany a very high rate of investment in GDP to produce rapid economic growth are considered below.

Recent experience of countries with high rates of economic growth

Turning to analysing post-World War II examples of sustained high economic growth, only 21 countries have achieved 8% growth a year sustained over a 20 year period since World War II. Leaving aside two extremely small states, Botswana (population 1.6 million) and Swaziland (population 1.1 million), which have economies dominated by individual projects, these countries that have undergone at least an 8% growth rate over a twenty year period fall into only two categories.

The first are eight Asian economies which have experienced prolonged periods of rapid growth - China, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, North Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, and Hong Kong. These form the primary focus of this study as their economies are not dominated by direct and indirect effects of the single commodity oil.

The second group are oil producers, or states adjacent to oil producers, in which rapid economic growth has been due to the direct and indirect effects of producing this commodity.[3] Growth rates based on oil are evidently not available to countries that do not have oil reserves and therefore do not form a generalisable model of development or are not immediately adjacent to countries which are large oil producers – for this reason the growth pattern of economies dominated by oil production are not considered in detail here.

Investment levels in the high growth Asian economies

To illustrate the decisive role played by high investment rates in sustaining high growth rates the percentage of Gross Fixed Capital Formation (fixed investment) in GDP for six of the eight high growth Asian economies is shown in Figure 2 - comparable IMF data for North Korea and Taiwan is not available. India has been added to this comparison due to the size of its economy and its recent rapid growth.

The evident feature of these economies countries is that all have had, during their periods of rapid growth, very high percentages of Gross Domestic Fixed Capital Formation in GDP. Taking the peak years for each country, Gross Domestic Fixed Capital Formation reached 35.6% of GDP in Hong Kong, 36.4% of GDP in Japan, 39.1% of GDP in South Korea, 41.6% of GDP in Thailand, 42.7% of GDP in China and 47.4% of GDP in Singapore.

Figure 2

It may be seen that no cases at all of rapid sustained economic growth without such a high rate of investment are to be found in such high growth economies. It is therefore evident that the economic evidence demonstrates that a high percentage of gross domestic fixed capital formation is a precondition for rapid economic growth. It is a high proportion of investment in GDP, not a high proportion of consumption, that forms the precondition for rapid economic growth.

Furthermore detailed examination makes clear that in those countries in which investment declined as a proportion of GDP – Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea and Singapore – this led to a marked decline in economic growth. On the contrary in those economies in which investment rose as a percentage of GDP, China and India, economic growth accelerated. The correlation between a high rate of growth and a high rate of investment is therefore evident.

In the data below the annual rate of growth is stated as the average over a five year period - in order to smooth out purely short term fluctuations in business cycles.

Japan

Measured in PPP terms Japan is Asia’s second largest economy. Japan’s rate of Gross Domestic Fixed Capital Formation peaked at 36.4% of GDP in 1973 but then fell to 23.3% of GDP by 2007.

Over the same period of time Japan’s annual rate of GDP declined from the 8.4% per cent rate in 1973 to only 2.1% (see Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3

Figure 4

South KoreaSouth Korea is the Asia’s 4th largest economy - after China, Japan and India. South Korea’s level of Gross Domestic Fixed Capital Formation in GDP peaked at 39.1% in 1991, although the 1996 level of 37.5% was only marginally lower.

Thereafter South Korea’s level of Gross Fixed Capital Formation declined sharply to 28.8% of GDP in 2007. South Korea’s annual rate of GDP growth fell in parallel from 9.4% in 1991, and 7.3% in 1996, to 4.4% in 2007 (see Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5

Figure 6

Thailand

Thailand’s percentage of Gross Domestic Fixed Capital Formation peaked at 41.6% of GDP in 1990 and 41.1% of GDP in 1995. It then fell to 26.8% of GDP in 2007.

Thailand’s annual rate of GDP growth over the same period fell from 10.9% in 1991, and 8.6% in 1995, to 5.6% in 2007 (see Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7

Figure 8

Singapore

Singapore saw one of the most sustained high levels of investment in GDP in any country in world history with more than 30% of GDP devoted to fixed investment for 30 years from 1970-2000. Singapore’s Gross Domestic Fixed Capital Formation peaked at 47.4% of GDP in 1984, remained at 38.7% of GDP in 1997 and fell to 24.9% of GDP in 2007.

Singapore’s annual rate of GDP growth over the same period fell from 8.5% a year in 1984, and 9.7% a year in 1997, to 7.1% a year in 2007 (see Figures 9 and 10).

Figure 9

Figure 10

Hong Kong

The percentage of Hong Kong’s GDP devoted to Gross Domestic Fixed Capital Formation, amid significant fluctuations, fell from 35.6% in 1964 to 35.6% and to 20.3% in 2007.

Hong Kong’s annual average growth rate fell from 10.5% in 1964 to 6.4% in 2007 (see Figures 11 and 12).

Figure 12

China and India

India and China show a clear contrast to Japan, South Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong.

Whereas in Japan, South Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong there was a decline in the proportion of the economy devoted to investment and a decline in the rate of economic growth, both India and China India have systematically increased the share of investment in their GDP and have seen an acceleration of their growth rates. Because this pattern in India and China is so strikingly different to Japan, South Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong it is worth looking at in some detail.

India’s Gross Domestic fixed Capital Formation increased from 17.9% of GDP in 1977 to 22.7% of GDP in 2000 and to 33.9% of GDP in 2007. By the third quarter of 2008, before the onset of the international financial crisis, India’s Gross Domestic Capital Formation reached 37.6% of GDP. Over the same period India’s annual GDP growth rate accelerated from 4.5% in 1977 to 6.0% in 2000 and to 8.8% in 2007.

Unlike those who advocate a reduction in investment and savings rates, Manmohan Singh, who is not only India Prime Minister but an excellently trained economist, has constantly stressed the need to raise India’s savings and investment rates and has made this a foundation of his economic policy – with considerable success, as has been seen, in terms of sustaining high growth rates.

Manmohan Singh considered China’s high savings and investment rates as the foundation of superior economic performance. For example in 2003 when asked, ‘is it legitimate to compare India and Chinese economies?,’ he replied: ‘There is nothing wrong in the comparison. It is good to try and achieve the growth rate of China. But we must remember that the Chinese savings rate is 42 per cent of the Gross Domestic Product, whereas savings in India is hovering at 24 per cent.’

Before he became Prime Minister in May 2004 Singh set out clearly the investment rate without which India’s target growth rate could not be achieved: ‘at a Delhi seminar, Dr Manmohan Singh spoke out regarding the targeted eight per cent growth rate in the Tenth Plan... he opined that an eight per cent growth rate would require a 30 per cent ratio of savings to income and a substantial rise in the tax-GDP ratio.’

Therefore in 2006, after assuming office, Prime Minister Singh noted with satisfaction the increase in India’s savings rate and set the goal of increasing it further together with a concomitant rise in the the investment rate: ‘Our statisticians now tell me that our savings rate has shot up in the last couple of years to about 27 to 28 percent of our GDP… we are a country where the proportion of young people to total population is increasing. All demographers tell me that if we can find productive jobs for this young labour force, that itself should bring about a significant increase in India's savings rate in the next five to ten years. If our savings rate goes up, let us say, in the next ten years, by 5 percent of GDP, we would have generated the resources for investment in the management of this new urban infrastructure that we need in order to make a success of our attempt at modernization and growth.’

By 2007 Prime Minister Singh therefore welcomed the further increase in India’s savings and investment rates. According to India’s premier financial paper, the Economic Times: ‘The investment and saving rate is as high as 35 percent of national economic output, Singh said at a meeting of his Congress party in this southern Indian city, the hub of a 50-billion-dollar IT industry at the vanguard of the country's economic resurgence.’

Similarly, India’s finance minister, P Chidambaram , called in February 2007 for a further increase in India’s savings and investment rates: ‘India’s savings and investment rate as percentage of GDP have gone up by 2 per cent each. But to sustain the revised growth rate of 9 per cent in the 11th Plan, he [ P Chidambaram] said: “Both savings and investment as proportion of GDP must be raised further.”

By February 2008 Prime Minister Singh noted the continued advance of the savings rate and the new high reached in India’s investment rate: ‘Highlighting the strong fundamentals of the economy, Dr. Singh said that the savings rate in the country has touched almost 35 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the investment rate is at an all time peak of over 36 per cent of the GDP.’

The orientation of India to very high savings and investment rates, and the relation of this to rapid economic growth, is therefore clear (see Figures 13 and 14)

Considering China its fixed investment increased from 27.8% of GDP in 1978 to 34.3% of GDP in 2000 and to 42.7 % of GDP in 2007 42.7%. In the same period China’s rate of GDP growth accelerated from 4.9% in 1978 to 8.6% in 2000 and to 10.8% in 2007.

Figure 13

Figure 14

Conclusion

The conclusion from economic evidence is therefore clear.

A high percentage of fixed investment in GDP is an indispensible precondition for a rapid rate of growth – there are no examples of countries with rapid rates of GDP growth and low proportions of the GDP devoted to fixed investment. It is a high level of investment in GDP, not a high rate of consumption, that is necessary for rapid GDP growth.

In those countries in which the rate of investment in GDP fell – Japan, South Korea, Singpore and Hong Kong – the rate of economic growth also fell substantially. In those countries – India and China – in which the percentage of GDP devoted to investment rose the rate of economic growth also increased.

In short all evidence establishes clearly that it is the high rate of investment which is decisive for rapid GDP growth.

This overwhelming factual evidence, of course, supports what is evident from a theoretical point of view. Consumption, by definition, does not add to productivity potential or production capacity and therefore increasing the rate of consumption does not raise GDP growth. If China lowers its proportion of the economy devoted to investment its economic growth rate will also fall - as is confirmed by the international experience noted above.

* * *

The paper draws on earlier material which appeared in 'Why Asia will continue to grow more rapidly than the US and Europe - a historical perspective' on the blog Key Trends in Globalisation.

References

[1] The figure for England for 1688 is that in Angus Maddison, The World Economy, OECD Paris 2006 p395. UK figures after 1688 and up to 1947 are calculated from One Hundred Years of Economic Statistics, The Economist, London 1989 p74. Figures from 1948 are calculated from International Monetary Fund, International Financial Statistics (August 2008) Minor adjustments have been made to chain the earlier statistics to be consistent with the IMF data – in no case does this make any significant difference to the pattern shown. The data for fixed investment for the earlier period used by The Economist One Hundred Years of Economic Statistics are based on calculations in C H Feinstein and Pollard Studies in Capital Formation in the United Kingdon 1750-1820, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1988. Other commentators have suggested that Feinstein and Pollard's figures are somewhat too high - see for example. N F R Crafts British Economic Growth during the Industrial Revolution, Clarendon, Oxford 1986 p73. None of these revisions and differences however is of sufficient magnitude to alter the fundamental pattern shown here.

US figures prior to 1948 are calculated from One Hundred Years of Economic Statistics, The Economist, London 1989 p74. Figures from 1948 are calculated from International Monetary Fund, International Financial Statistics (August 2008) Data for the earlier period give only private fixed capital formation whereas that after 1948 is for total fixed capital formation – i.e. including government fixed capital formation. There are no reliable estimates of government fixed capital formation in the earlier period and therefore data for the earlier period have been adjusted upward by the difference between the two in 1948 – which is slightly over two per cent of GDP. This has the effect of revising upwards slightly the percentage of GDP allocated to fixed investment in the earlier period but the difference is too small to affect the overall pattern.

Figures for Germany prior to 1960 are calculated from One Hundred Years of Economic Statistics, The Economist, London 1989 p202. Figures from 1960 are calculated from International Monetary Fund, International Financial Statistics(August 2008). There is however no significant statistical difference between the two.

Figures for Japan, South Korea, China, India and Vietnam calculated from International Monetary Fund, International Financial Statistics.

[2] Phyllis Deane and W A Cole in British Economic Growth 1688-1959, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1980 p2 being closer to the lower figure while further studies have tended to revise the figure upwards slightly. The higher estimates for the earlier period have been taken here so as to avoid any suggestion of exaggerating the degree to which the proportion of GDP devoted to Gross Domestic Fixed Capital Formation has risen. The precise figure used here is that calculated by Maddison in Angus Maddison, The World Economy, OECD Paris 2006 p395. The higher figure, as can be seen, makes no difference to the overall trend.

[3] These countries are Iran, Iraq, Equatorial Guinea, Kuwait, Israel, Jordan, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Libya, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, and the United Arab Emirates.

No comments:

Post a Comment