By Michael Burke

The UK trade gap widened in November to £4.1bn. The trade gap is clearly on a widening trend. The latest deficit compares to a deficit of £2.3bn in November 2009. Taking the latest 3 months data together to smooth the volatility of monthly data, the trade gap was £12.2bn, compared to £7.8bn for the same period in 2009. The total trade deficit in goods and services for 2009 was £29.7bn. But the deficit in the first 11 months of this year is £41.3bn, and may threaten the record annual deficit of £43bn at the height of the boom in 2007.

The chart below shows the monthly trade deficit from 2007.

Figure 1

Government forecasts for sustained economic recovery are based on export-led growth. Exports are growing, and much more strongly than forecast by the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR). At the time of the June Budget the OBR forecast a 4.3% rise in exports in 2010. But in the latest 3 months exports are 10.3% higher than a year ago as world trade has recovered. Exports have reached a new peak reflecting the upturn in demand in key export markets and are now 3.2% above the previous high seen in 2008.

However, imports are rising still more strongly. In June the OBR forecast a 5.6% rise in exports in 2010. But in the latest 3 months exports are 13.5% higher than a year ago as demand for imports has significantly outstripped export growth.

As SEB has previously warned, without any rise in investment the British economy would tend to become even more uncompetitive, and any new upturn in demand would lead to a widening of the deficit. Imports in any economy are either directly consumed or used as inputs for production. The deficit in finished manufactured goods – a key component of directly consumed imports – was £15.1bn in November, a large multiple of the total deficit. The deficit in this category is both chronic and acute.

The rational response to this situation would be a sharp increase in investment to improve competitiveness combined with a Sterling depreciation. But unlike other categories of economic activity private investment has barely recovered and now accounts for £40.4bn of the £54.3bn loss in output since the recession, three-quarters of the total.

Yet there is now a growing lobby to raise interest rates in order to increase the value of Sterling. Andrew Sentance, one of the members of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee has repeatedly voted and campaigned for higher rates and now leads a chorus of City-based economists calling for higher rates , even though unemployment is rising and the economic outlook is far from benign.

This campaign, which has received the support of David Cameron is cloaked in terms of combating inflation, but the VAT hike will contribute to rising prices. Other administered prices rises such as rail, bus tube fare increases and the inflation-plus hike in utility bills have the same effect, and could all be avoided by different policy choices. The campaign’s aim is to increase the value of Sterling, irrespective of the effect on the trade balance and the competitiveness of local production – and it is increasingly embraced by the financial sector and the Tory-led government.

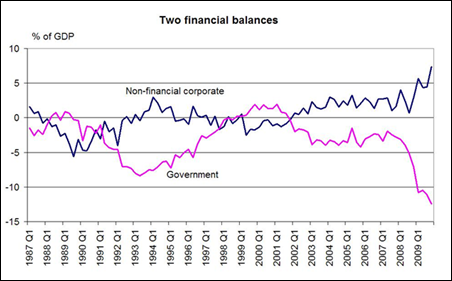

This is because the private sector is running a very large surplus, as shown in the chart below, reproduced from this website.

Figure 2

This surplus is not being invested in productive investment in the British economy. The cash balances are being held in British banks, and they in turn want to invest these in overseas financial assets. But much better to invest those with a strong pound than a weak one- the same funds will buy more assets if the currency is overvalued. Typically, a build-up in these corporate surpluses is followed by policies to increase the value of the pound, including higher interest rates.

Once again, the City and the Tory government are moving towards adopting a policy to meet the interests of the banks with no care for the outlook for jobs, investment and the economy as a whole.

No comments:

Post a Comment