By John Ross

Given the onset of a renewed round of the international financial crisis it is useful to draw together its various elements in an analysis of its overall determinants, its course, and the policies necessary to deal with it. This is the aim of this article.

* * *

For the second time in three years almost all parts of the world economy are being shaken by a renewed financial and economic crisis. The most important immediate drivers of this are not Standard and Poor's downgrading the US's credit rating, or political struggles between President Obama and Republicans in Congress, but weak US economic recovery, Europe's widening debt crises, the consequent $8 trillion loses on international share markets by 9 August with knock on effects on balance sheets and spending, the continuing decline of US house prices and a new developing crisis of the banking system.

Reasons for the open reappearance of crisisThe reason severe crisis has reappeared, and what determines its dynamic, is the failure of US and European government policies to resolve the issues which created 2008's financial collapse. The policies pursued since then, which were adapted to deal with much more minor economic events than the ones which occurred, postponed the unwinding of the crisis without removing its underlying causes. As a result the focus of the crisis changed but it was not resolved.

The immediate cause of the financial crash of 2008 was an unsustainable build-up of US private sector debt – this debt being accumulated due to the attempt to maintain the growth of the US economy and to ensure political stability by sustaining US living standards. By the 4th quarter of 2007, the peak of US economic expansion, total US household, private non-financial company, and government debt was 218 per cent of US GDP – Figure 1. That the fundamental debt build up was private, and not government, is shown by the fact that household and non-financial company debt was equivalent to 168 per cent of GDP compared to 51 per cent of GDP for government debt - i.e. private debt was more than three times as large as government debt.

Figure 1

Interest rate increases introduced leading to 2008, in order to deal with inflation, resulted in the inability of the US private sector to finance this debt burden. The US sub-prime mortgage crisis was simply the weakest link in the overall excessive US private debt.

In 2008 the inability of the US private sector to meet its debt obligations, with consequent falls in asset values, initially in housing and then in shares and other financial instruments, destroyed US financial institutions’ balance sheets. The US financial sector overall became insolvent. Therefore a stronger and more centralized financial instrument, the US state, had to step in to rescue the private financial system - with a similar process occurring in other countries. The new crisis has broken out because of the risk that the tools available to the US and European states themselves will be insufficient to restore stability.

Transfer of private sector debt into the public sectorThe debt data clearly show the process of transfer of the original excessive US private debt into the public sector – the changes in US debt since the peak of the previous business cycle are shown in Figure 2.

Following the onset of the US economic downturn in 2008, the overall US debt burden rose, reaching 247 per cent of GDP in the 3rd quarter of 2009 – these changes reflecting the decline in US GDP as well as increasing debt. Since then up to the 1

st quarter of 2011, the latest available data, US debt fell only marginally to 243 per cent of US GDP - still 26 percentage points above pre-recession levels.

However the internal structure of US debt shifted. US private sector debt peaked at 180 per cent of GDP in the 2nd quarter of 2009. It then fell to 163 per cent of GDP – still 5 percentage points above its pre-recession level. But any recent decline in private sector debt has been almost entirely offset by increases in government debt created by budget deficits exceeding 10 per cent of GDP.

Figure 2

The US therefore simply ‘nationalized’ its debt problem – replacing private with public debt. The mechanisms by which this occurred were the indirect consequences of the financial crisis, with recession increasing welfare payments and reducing tax receipts, as well as transfer of funds to the private sector in bank bailouts and similar measures.

John Mauldin and Jonathan Tepper therefore put it correctly in their book Endgame: ‘Debt is moving from consumer and household balance sheets to the government. While the debt supercycle was about the unsustainable rise of debt in the private sector, endgame is the crisis we will see in the public sector debt.’ (p25)

In short, although the US crisis may currently appear in the form of a government deficit and debt issue, the origins of the problem lay in the private sector and the government debt issue is the consequence of nationalization of private sector debt.

The European debt crisis

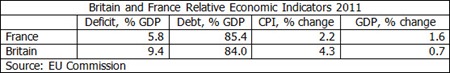

Europe followed a similar path to the US but with some countries, e.g. Greece and Italy, building up large public sector debts alongside the private ones in Spain and other states. Europe’s situation is structurally more potentially threatening than the US as the Federal Reserve has greater resources than the European Central Bank and the US state is able to react in a more centralized way than the decentred structure created by the different states of the European Union.

The European Central Bank simply does not have sufficient resources to be able to deal with a spread of the debt crisis into the larger EU economies such as Spain and Italy. Given the exposure of European banks to national state debt the spreading of the European sovereign state crisis to major economies therefore has the potential to bring down the European banking system. For this reason there have been rising European interbank lending rates, reflecting banks decreasing willingness to lend to each other, extremely high rates for bank insurance in a number of countries, and sharply falling bank share prices in both Europe and the US.

Kenneth Rogoff, author of the notable quantitative study of debt crises

This Time is Different, and former chief economist of the IMF, accurately summarized the situation in the financial sector as follows:

‘Securitization, structured finance, and other innovations have so interwoven the financial system’s various players that it is essentially impossible to restructure one financial institution at a time. System-wide solutions are needed… the financial system remains on government respirators… in the US, UK, the euro zone, and many other countries today.

‘Most of the world’s largest banks are essentially insolvent, and depend on continuing government aid and loans to keep them afloat. Many banks have already acknowledged their open-ended losses in residential mortgages. As the recession deepens, however, bank balance sheets will be hammered further by a wave of defaults in commercial real estate, credit cards, private equity, and hedge funds. As governments try to avoid outright nationalization of banks, they will find themselves being forced to carry out second and third recapitalizations.

‘Even the extravagant bailout of financial giant Citigroup, in which the US government has poured in $45 billion of capital and backstopped losses on over $300 billion in bad loans, may ultimately prove inadequate.’

Political struggles are the symptom of the renewed crisis and not its causeGiven the scale of the debt situation none of the means used for tackling the debt problem in the US and Europe can avoid severe economic pain. The political fighting which has broken out is simply over how this pain should be shared. The political struggles which have occurred, for example between President Obama and Republicans in Congress, or between Germany’s government and other European states, are therefore not the cause of the renewed economic crisis but its result. Analysing the different responses however leads directly to the issue of the necessary policies to deal with the financial and economic crisis.

The necessity to run budget deficitsThe most ideologically right wing forces - the US Tea Party and those in Europe sharing the views of the British Conservatives - advocate limiting the public debt build up by radically reducing government spending. This is linked to a theory that the state is ‘crowding out’ the private sector. This entire analysis is false. Because of its ideological blinkers it fails to see that the origin of the crisis lay in the private sector debt. It is also extremely dangerous in terms of economic policy.

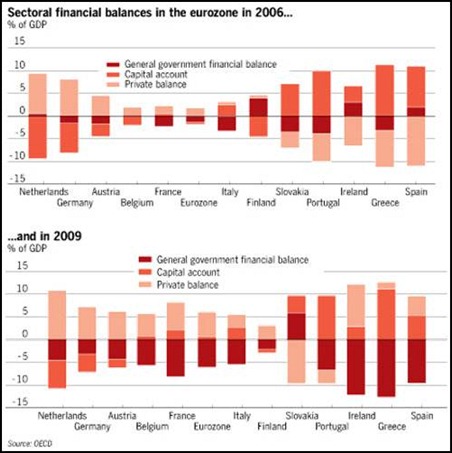

The main transmission belt from excessive debt into recession is the fall in

private investment. As may be seen in Figure 3 the entire decline in GDP in the G7 economies between the 1

st quarter of 2008, the peak of the previous business cycle, and the 1

st quarter of 2011, the latest available data, was accounted for by the decline in fixed investment. In fixed price parity purchasing powers (PPPs) the decline in G7 GDP was $381 billion and the decline in fixed investment was $591 billion – the decline in fixed investment can be greater than the decline in GDP as it is offset by increases in household and government consumption.

Figure 3

The theory of ‘crowding out’ argues that resources used to finance the budget deficit would be used to generate economic expansion if released to the private sector – for example US financial analyst John Mauldin argues ‘increasing government debt crowds out the necessary savings for private investment, which is the real factor in increasing productivity.’ (

Endgame p59)

But reducing budget deficits by cutting public spending cannot create an economic way out in present conditions. Reducing budget deficits cuts demand. But resources released to the private sector are used to pay down debt, so private spending will not increase sufficiently to compensate for the fall in public spending. Total demand will fall, increasing recessionary pressure.

In short, it is vital in the short term to maintain budget deficit spending, including by targeting maintaining or expanding consumption – state spending on investment is analysed below. Attempts to immediately reduce budget deficits must be strongly resisted. Countries facing an economic slowdown should run, or increase, budget deficits to compensate for the shortfall of private sector demand.

Richard Koo, in his important books Balance Sheet Recession and The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics, has dealt with this correctly in analysing the experience of the decades long fight against the consequences of over-indebtedness in Japan. As Koo noted:

‘What sets Japan’s Great Recession apart from the U.S. Great Depression is that Japanese GDP stayed above bubble peak levels in both nominal and real terms despite the loss of corporate demand worth 20 per cent of GDP and national wealth worth ¥1,500 trillion… The financial deficit of the government sector mounted sharply, leaving in its wake the national debt we face today. But it was precisely because of these expenditures that Japan was able to sustain GDP at above peak-bubble losses despite the drastic shifts in corporate behavior and a loss of national wealth equivalent to three years of GDP. Government spending played a critical role in supporting the economy…

‘Japan was left with a large national debt. But if the government had not responded with this kind of stimulus, GDP would have fallen to between one-half and one-third of its peak – and that is an optimistic scenario. U.S. GNP shrank by 46 per cent after falling asset prices destroyed wealth worth a year’s worth of 1929 GNP during the Great Depression, and the situation in Japan could easily have been much worse. This outcome was avoided only because the government decided early on to administer fiscal stimulus and continue it over many years…

‘In summary, the private sector felt obliged… to pay down debt… Disastrous consequences were avoided only because the government took the opposite course of action. By administering fiscal stimulus, which was also the right thing to do, the government succeeded in preventing a catastrophic decline in the nation’s standard of living despite the economic crisis.’ (

The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics p22-25)

Naturally the form the budget deficit takes is itself extremely important. Government spending on those on average and low incomes, and on investment, is not only socially more just but is far more effective as a stimulus than tax cuts for the best-off – who save, rather than spend, a higher proportion of their income. Equally spending on investment is far more effective in expanding the economy that military spending – which does not add to productive capacity. But overall it is necessary to fight moves by fiscal conservatives to reduce the budget deficit in the short term. As an immediate response to the financial crisis countries facing the threat of economic downturn should run or maintain stimulus packages funded, if necessary, by budget deficits.

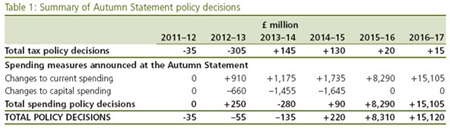

Budget deficit and the medium termWhile budget deficits with a large component targeted at maintaining consumption are immediately vital to prevent short term economic decline they are not sufficient, faced with deep economic problems, to relaunch substantial growth because they do not deal with the most fundamental issue driving the downturn – the investment fall. This is in addition to the fact that few countries have Japan’s financial strength, which enabled it to sustain a very large budget deficit over a long period. For most countries large budget deficits can be run in the short term but are financially unsustainable in the medium term.

A policy of running large budget deficits is often

inaccurately described as a 'Keynesian' one - inaccurately as Keynes own central concern was factors affecting investment and not budget deficits.

1 Paul Krugman in the

New York Times, for example, regularly but wrongly argues that the budget deficit is both the most central issue in economic policy and the core of Keynes views. US economist Paul Davidson similarly claims in

The Keynes Solution: ‘Anything that increases spending on goods and services increases the profitability of business firms and the hiring of workers.’ (p54) But this is false - for example, an increase in spending on goods and services accompanied by cost increases may lead profits to fall.

However, even if profit did increase due to increases in demand, companies may not reverse the cuts in investment that are the core of the recession. Keynes pointed out that to generate investment a price must be paid to overcome ‘liquidity preference’ - the advantages of holding assets in cash and other liquid forms. In circumstances of high uncertainty, such as at present, the cost of overcoming liquidity preference may be prohibitive and therefore it will prevent investment taking place even if such investment would yield a positive profit.

Low interest rates necessary but not sufficientEven more fundamental than liquidity preference in the present situation is that, given excessive indebtedness, companies use resources to repay debt, that is to build up their balance sheets, and not to invest even if demand increases. Therefore stimulating demand by budget deficits may prevent worse declines in production but does not produce significant output increases.

In such conditions low interest rates are also insufficient as an economic policy to provide a way out. Low interest rates are necessary to prevent interest payments becoming unsupportable and to remove a block to borrowing for investment. But they do not lead to investment under conditions where companies are intent on paying down debt and have no intention of borrowing for investment.

International redistribution of debt

As any solution to the present situation must involve medium term debt reduction a number of states are seeking to achieve this at the expense of other countries even without formal defaults on debt payments. In particular the US, via falls in the exchange rate of the dollar, reduces the real value of its debt at the expense of countries which hold dollar assets. Such policies however clearly only aid one country at the expense of others, effectively redistributing the debt without reducing the overall debt burden.

Inflation is not a relatively harmless solution

It is important to remove an illusion currently being suggested that inflation would be a relatively painless and non-harmful way to reduce debt. The idea behind this is that while the monetary volume of debt, its nominal value, would remain the same its real size would be reduced.

Kenneth Rogoff, for example, has argued this:

‘It is time for the world’s major central banks to acknowledge that a sudden burst of moderate inflation would be extremely helpful in unwinding today’s epic debt morass…. Moderate inflation in the short run – say, 6% for two years – would not clear the books. But it would significantly ameliorate the problems, making other steps less costly and more effective. ‘

Similarly the British economist

Will Hutton has argued:

‘As the IMF's chief economist, Olivier Blanchard, has suggested, if the options are public and private default, continuing bank weakness, economic stagnation (perhaps depression), or inflation, then the least bad option is to accept inflation, but to manage it within bounds.

‘Since inflation will happen anyway as governments seek the least bad way out, the choice in reality is whether to accept and manage it or not. Once debt is at a sustainable level and growth has resumed, then the world's financial system can be redesigned to avoid a repeat, and price stability restored.

‘This is the truth that cannot speak its name: as a senior financial policy official told me, even to raise it at home or abroad merely as an issue for debate is to invite universal disapproval. But truth must be faced. Britain should provide a lead – both for its own economic fortunes and to set the new international standard. As a minimum it should announce a new programme of quantitative easing, in effect printing money; insist the Bank of England uses the money it prints to buy the broadest range of private debt; and immediately replace the 2% inflation target with a target for the growth of money GDP – so getting Britain off the hook of its unpayable private debts.’2

However someone will have to suffer the loss in real resources created by the inflation. Usually this is the majority of the population as the rate of increase of incomes fall behind the rate of inflation. Politically a policy of lowering debt by inflation is therefore likely to be drastically unpopular for whoever implements it.

Furthermore economically inflation, striking at the majority of the population by reducing living standards, will actually cut consumption – which strengthens recessionary tendencies. Inflation also does not deal with the issue of increasing investment – the fall in which drove the recession. In short inflation is not a solution either politically or economically to a crisis of the depth which currently exists.

Indirect means of stimulating investmentIf the way out is turned to, the necessary policies cannot be separated from the analysis of the depth of the crisis.

If the current economic crisis were of small or moderate dimensions then it could indeed be tackled by increases in budget deficits which primarily raised or maintained consumption. Such deficits would increase demand while liquidity preference, lack of profitability and debt levels would be insufficient to prevent companies responding to the increase in demand by raising investment - therefore substantial economic recovery would occur. This, however, has clearly not occurred in the crisis since 2008 despite large budget deficits being run.

Given budget deficits have been insufficient, attempts are also made to raise investment by extremely low interest rates and by seeking to reduce liquidity preference – the latter being a key goal of the talk regarding the need to ‘restore confidence’. These measures have also clearly not succeeded.

Confronted with this impasse more logical economic commentators are therefore beginning to address the need to raise investment. Such discussion currently primarily centres on advocating indirect means such as tax breaks. For example

Joseph Stiglitz recently argued:

‘those worried about the shortage of policy instruments are partially correct. Bad monetary policy got us into this mess but it cannot get us out. Even if the inflation hawks at the Federal Reserve can be subdued, a third bout of quantitative easing will be even less effective than QE2. Even that probably did more to contribute to bubbles in emerging markets, while not leading to much additional lending or investment at home.

‘The Fed’s announcement that it will keep the target federal funds rate near zero for the next two years does convey its sense of despair about the economy’s plight. But, even if it succeeds in stopping, at least temporarily, the slide in equity prices, it won’t provide the basis of recovery: it is not high interest rates that have been keeping the economy down. Corporations are awash with cash, but the banks have not been lending to the small and medium-sized firms… The Fed and Treasury have failed miserably in getting this lending restarted, which would do more to rekindle growth than extending low interest rates though 2015.

‘But the real answer, at least for countries such as the US that can borrow at low rates, is simple: use the money to make high-return investments. This will both promote growth and generate tax revenues, lowering debt to gross domestic product ratios in the medium term and increasing debt sustainability. Even given the same budget situation, restructuring spending and taxes towards growth – by lowering payroll taxes, increasing taxes on the rich, as well as lowering taxes for corporations that invest and raising them on those that do not – can improve debt sustainability.'

By identifying raising investment as the key target Stiglitz does address the central dynamic of the recession. But the issue is once again quantitative and related to the depth of the crisis. Will measures such as tax breaks be sufficient to raise investment if they are added to other policies such as running budget deficits and low interest rates? If the economic crisis is not deep they will suffice. If the economic crisis, and the necessity to pay down debt, is stronger then indirect measures to target investment, such as tax breaks, will not be sufficient.

The current indications, given the scale of the economic problems and debt burden, is that indirect means to stimulate investment by policies such as tax breaks will be insufficient to relaunch substantial economic growth.

Direct means of raising investmentThe most decisive way to overcome the current situation flows from the above trends. Its practical effectiveness was shown by its use by China in its successful 2008 stimulus package, which was followed by over 30 per cent GDP growth in three years. Keynes also analysed and advised it. This is that the state must overcome the reality or threat of a fall in investment by itself undertaking and organizing investment. Keynes noted this in

The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money: ‘It seems unlikely that the influence of banking policy on the rate of interest will be sufficient by itself to determine an optimum rate of investment. I conceive, therefore, that a somewhat comprehensive socialization of investment will prove the only means of securing an approximation to full employment.’ (p378)

Such an analysis flowed from Keynes practical experience regarding the relation between the depth of economic crisis and lack of sufficient efficacy of other economic instruments: 'Only experience… can show how far management of the rate of interest is capable of continuously stimulating the appropriate volume of investment… I am now somewhat sceptical of the success of a merely monetary policy directed towards influencing the rate of interest… I expect to see the State… taking an ever greater responsibility for directly organising investment; since it seems likely that the fluctuations in the market estimation of the marginal efficiency of different types of capital… will be too great to be offset by any practicable changes in the rate of interest.' (p164) Therefore: ‘‘I conclude that the duty of ordering the current volume of investment cannot safely be left in private hands.’ (p320)

Keynes naturally did not advocate an administered economy. But he therefore explicitly argued in the

General Theory that the state should have the ability to intervene sufficiently to determine overall investment levels.Keynes also noted that this 'somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment' and 'the duty of ordering the current volume of investment'

did not mean the elimination of the private sector, but socialised investment operating together with a private sector: 'This need not exclude all manner of compromises and devices by which public authority will co-operate with private initiative… apart from the necessity of central controls to bring about an adjustment between the propensity to consume and the inducement to invest there is no more need to socialise economic life than there was before…. The central controls necessary to ensure full employment will, of course, involve a large extension of the traditional functions of government.' (p378)

The country which most approximates to this economic system is China. China, of course, describes its economy in a different way and using Marxist terminology. China defines itself as passing through ‘the primary stage of socialism’ and its overall system as ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’. However it is not the important question whether China’s definition of its own system should be accepted, or whether its economy should instead be regarded as conforming in important features to the system described by Keynes in the

General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. What is important is understanding how such an economic system works and to note that China has been able to run the world’s largest stimulus package without an unsustainable

budget deficit, and why its macroeconomic policy has come through the international financial crisis more successfully than the US and Europe – and why China’s economic system has generated, during the last thirty years, the most rapid economic growth of any major economy in the world.

China’s economy

The difference between China and the US and Europe, of course, lies in economic structure. After its 1978 economic reforms China abandoned an administered economy. But it did not abandon the ability of the state to set the overall level of investment, and it maintains a state owned banking system which is stronger in a crisis than the ones in the US and Europe and which can be instructed to expand lending in order to sustain stimulus packages. China therefore actually implements Keynes point that ‘the duty of ordering the current volume of investment cannot safely be left in private hands.’ That is, a ‘somewhat comprehensive socialization of investment’ does exist in China, not in the sense that the private sector is eliminated, on the contrary China’s private sector is large and dynamic, but in the sense that the state has sufficient levers to determine the overall level of investment. In contrast in the US and Europe the conditions outlined by Keynes do not exist, and the state sector is insufficiently large to deliver an investment-led stimulus.

As a conseuence of these differences China has come through the financial crisis far more successfully than the US or Europe

Implication of the differencesOnce again the interaction of these different factors cannot be separated from analysis of the scale of economic crisis itself. China’s economic structure clearly gives it a superiority which has allowed it to avert serious downturns, as shown both in the 1997 Asian debt crisis and in the international financial crisis since 2008, and to maintain very long term rapid economic growth. But how serious the lag in the US and Europe compared to China is depends on how serious the economic crisis is.

If the economic crisis is not deep then gradually time, and greater application of the measures which are available to the US and European economies – budget deficits, low interest rates, tax breaks for investment – will overcome the investment decline. China will still grow more rapidly, but the US and Europe will also resume growth. If the crisis is deep then only adoption of full scale Chinese methods of direct state action to implement ‘the duty of ordering the current volume of investment’ would suffice. That, however, would require a huge extension of the state sector of the economy, and therefore greater application of the indirect methods available in the US and Europe will be tried first.

One clear implication, of course, is that in all these different circumstances China continue to will grow much more rapidly than the US and Europe even if the latter escape a 'double dip' recession.

ConclusionThe realistic conclusions which follow from the present renewal of the international financial crisis, in terms of both analysis and the required policy response, are therefore clear:

- The International financial crisis has recurred because the economic policies to deal with the 2008 crash in the US and Europe did not remove its underlying cause - excessive debt build up in an attempt to sustain US economic growth and living standards. The post-2008 policies failed because they were designed to deal with much less serious economic events than the ones which unfolded.

- The effect of the policies pursued after 2008 has been to nationalize large part of the debt that originated in the private sector. Therefore, in most cases, and in particular in the US, even if the crisis reappears around state finances the actual origins of the problem lay in the private sector debt.

- The strategic failure to overcome the debt crisis creates strong pressure to a renewed crisis of the banking system.

- The debt crisis transmits itself into the real economy above all though a collapse in investment – taking the G7, the entire decline in GDP is due to the fall in fixed investment.

- In the short term it is necessary to deal with the crisis by continuing to run budget deficits, and countries that have not done so may well need to introduce budget deficit spending. China is an exception because its economic structure allows it to run large stimulus packages without budget deficits due to its ability to directly stimulate investment. Only a handful of other countries, however, have a state sector large enough to fund and run such investment programmes and therefore other economies will have to run budget deficits in the short/medium term. However while budget deficits are necessary to avoid sharp economic decline the experience of the last three years has shown that the economic crisis is too deep for budget deficits by themselves to stimulate significant growth because they do target the core of the recession, the investment decline.

- Very low interest rates must be maintained in order to lighten the burden of interest payments on the overextended debt, and to remove an obstacle to investment. However, once again the experience of the last three years has shown that the economic crisis is too deep for low interest rates themselves to relaunch investment and substantial economic growth.

- China possesses the advantage that it can directly stimulate investment. In other countries there is also a growing realisation that the core transmission of the economic problem lies in investment falls. But without a sufficiently large state sector most other countries do not have the means to directly launch investment. Therefore indirect methods such as tax incentives for investment and similar measures are being proposed. It remains to be seen in practice, if these are introduced, whether they are effective. Given the depth of the crisis the probability is that even if such measures are introduced they will not be enough to sufficiently overcome the low investment level. Consequently growth will continue to be very slow in the US and Europe even if a new recession can be avoided.

- The world economy will therefore see a further period in which China’s economy will grow rapidly while the US and Europe remain at best relatively stagnant.

* * *

This article originally appeared on

Key Trends in Globalisation.

Notes1. See Ross, J. ‘Deng Xiaoping and John Maynard Keynes’. Soundings Winter 2010.

2. The British newspaper

The Observer made the same call:

‘The only alternative to default is inflation – governments printing money to get out of the corner they, their banks and their citizens are in. The question facing policymakers in the years ahead will be which of the unpalatable options they confront – economic stagnation, public and private default together with endemic bank weakness, or uncontrolled or managed inflation – they are going to choose…

‘The British government's policies are locked in the same impotent stasis as the rest of the world's – battening down the hatches, cutting public spending and borrowing, and refusing to accept realities. The government should declare independence. It should abandon the suffocating 2% inflation target and replace it with a target for the total volume of spending in the economy. It should prepare to stimulate the economy with more quantitative easing – in effect printing money – using the proceeds to lend directly to public agencies and departments prepared to lift capital spending.’